In 1657 William Worcester, the constable, brought Samuel Newman, alehouse keeper, before the magistrates for allowing Richard Wills and Samuel Brabson to continue drinking late into the night at his alehouse. He wasn’t the first Newman in the village to keep an alehouse and turn an occasional blind eye to the law.

In 1657 William Worcester, the constable, brought Samuel Newman, alehouse keeper, before the magistrates for allowing Richard Wills and Samuel Brabson to continue drinking late into the night at his alehouse. He wasn’t the first Newman in the village to keep an alehouse and turn an occasional blind eye to the law.

Over 70 years earlier, at the same court in 1581 that ordered villagers not to wander about carrying fire in wisps of straw, Robert Newman, common maltster and ale seller, was accused of breaking the assize of ale (i.e. selling short measure) and fined two pence.

A couple of generations later, in 1630, Henry Newman of West Haddon was granted an alehouse licence. Possibly Henry was Samuel’s father.

40 years after the fire another rare survival of a West Haddon manorial court roll records the proceedings on 29 April 1698. The court was held at Samuel Newman’s (probably by this time the son of Samuel Newman senior – though the old man was still alive). There was no manor house in West Haddon – a pub was one of the few public gathering places in the village where such a meeting could be held. On this occasion, under his own roof, Samuel Newman was fined a shilling for selling ale in short measures.

40 years after the fire another rare survival of a West Haddon manorial court roll records the proceedings on 29 April 1698. The court was held at Samuel Newman’s (probably by this time the son of Samuel Newman senior – though the old man was still alive). There was no manor house in West Haddon – a pub was one of the few public gathering places in the village where such a meeting could be held. On this occasion, under his own roof, Samuel Newman was fined a shilling for selling ale in short measures.

In his will Samuel junior left the pub to his son (another Samuel), who died, young and unmarried, leaving it to his sisters Sarah and Alice who, in 1750, along with their younger brother John, sold it to William Gulliver. In its first appearance in the deeds the pub is called The Cock.

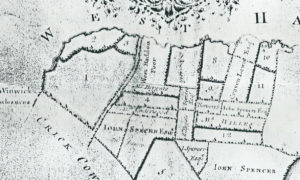

Samuel Newman was one of those whose houses were burned down in 1657. It would be a reasonable assumption to suppose that the houses were all adjoining or close to each other. Pinning down the location of The Cock might identify the location of the fire. And it so happens that through the deeds we can do that. The Cock must have been rebuilt after the fire. And it was rebuilt again, in 1828, before being sold ten years later under its new name, The Wheatsheaf.

That brings to an end this commemoration of the 1657 Great Fire of West Haddon. The blog will continue, on an occasional basis, shooting off at whatever historical tangent captures my attention at the time. If you have been, thanks for reading.

When Edward junior came to rebuild he would almost certainly have had the roof thatched. It was the most common roofing material in village housing at this period. And the upper rooms in most houses would have been open to the rafters too – no plastered ceilings to hold back the flames if a fire took hold.

When Edward junior came to rebuild he would almost certainly have had the roof thatched. It was the most common roofing material in village housing at this period. And the upper rooms in most houses would have been open to the rafters too – no plastered ceilings to hold back the flames if a fire took hold. few pennies in it. But people could get careless. And the spring and summer of 1657 were both extraordinarily hot. By August 1st all the thatch in the village must have been as dry as tinder…

few pennies in it. But people could get careless. And the spring and summer of 1657 were both extraordinarily hot. By August 1st all the thatch in the village must have been as dry as tinder… Downstairs there was a hall (the main living room) which had a table, a form (a kind of bench) and three stools in it – no chairs. In the parlour (the best room) there was a bed, three coffers, three barrels and a thrall to stand them on. This was a room for entertaining visitors. It was usual at this period for the best bed to stand in the parlour, usually with bed curtains, displaying the wealth of the family by the quality of the fabric or the richness of the embroidery. (Visitors may have been offered ale, but it seems they were expected to stand.) The kitchen held the usual food-related equipment of the period. But there was only one chamber, or upstairs room. This held two more beds and a couple more coffers. The furniture was valued at a lot less than the household linens and bedding – the table, stools etc were worth ten shillings (50p), the brass and pewter ware £2, while the mattresses, blankets, sheets and pillows, tablecloths and napkins amounted to £8!

Downstairs there was a hall (the main living room) which had a table, a form (a kind of bench) and three stools in it – no chairs. In the parlour (the best room) there was a bed, three coffers, three barrels and a thrall to stand them on. This was a room for entertaining visitors. It was usual at this period for the best bed to stand in the parlour, usually with bed curtains, displaying the wealth of the family by the quality of the fabric or the richness of the embroidery. (Visitors may have been offered ale, but it seems they were expected to stand.) The kitchen held the usual food-related equipment of the period. But there was only one chamber, or upstairs room. This held two more beds and a couple more coffers. The furniture was valued at a lot less than the household linens and bedding – the table, stools etc were worth ten shillings (50p), the brass and pewter ware £2, while the mattresses, blankets, sheets and pillows, tablecloths and napkins amounted to £8! The chest was broken up and the locks broken when the King’s army came into these parts and the deeds and evidences taken away and stolen, which the trustees believe was done by Samuel Clerke himself (he being a notorious cavalier attending the King’s army.) So, in effect, Vicar and village were claiming loyalty to the parliamentary (winning) side. How convenient.

The chest was broken up and the locks broken when the King’s army came into these parts and the deeds and evidences taken away and stolen, which the trustees believe was done by Samuel Clerke himself (he being a notorious cavalier attending the King’s army.) So, in effect, Vicar and village were claiming loyalty to the parliamentary (winning) side. How convenient. Later an adjoining close over the parish boundary in Silsworth, Watford, was added to the estate. It was administered by a group of trustees – some of their names are already familiar to us – Gulliver, Wills, Gutteridge, Worcester, Miller, Ward and Elmes.

Later an adjoining close over the parish boundary in Silsworth, Watford, was added to the estate. It was administered by a group of trustees – some of their names are already familiar to us – Gulliver, Wills, Gutteridge, Worcester, Miller, Ward and Elmes.

there were yards outside and possibly a barn and outbuildings – there was certainly a cowhouse. Elizabeth also inherited a couple of milk cows, various sheep, a hog and chickens, along with quantities of rye, wheat, barley and pease (dried peas were used to make pease pudding and could also be used as winter fodder, haulms and all, for livestock), and butter and cheese. Four hives of bees were to be divided between his wife and his executor.

there were yards outside and possibly a barn and outbuildings – there was certainly a cowhouse. Elizabeth also inherited a couple of milk cows, various sheep, a hog and chickens, along with quantities of rye, wheat, barley and pease (dried peas were used to make pease pudding and could also be used as winter fodder, haulms and all, for livestock), and butter and cheese. Four hives of bees were to be divided between his wife and his executor. of estrangement between them. He also names five married daughters, so he may have been quite old and already have settled farmland etc on his son as he came of age or married. However it is interesting that he appointed one of his sons in law as his executor, rather than Gregory, while another son in law got £5, my best hive of bees and a brass pan.

of estrangement between them. He also names five married daughters, so he may have been quite old and already have settled farmland etc on his son as he came of age or married. However it is interesting that he appointed one of his sons in law as his executor, rather than Gregory, while another son in law got £5, my best hive of bees and a brass pan. Over the next 30 years his son, Bartin junior, increased his land ownership in West Haddon to nearly 50 acres with a 10 acre freehold in Silsworth and a lease on a further six acres.

Over the next 30 years his son, Bartin junior, increased his land ownership in West Haddon to nearly 50 acres with a 10 acre freehold in Silsworth and a lease on a further six acres. Although Richard earned his living as a tailor, he seems to have had some livestock too, leaving a ewe and lamb to one of his step-daughters and a hoggrill sheep to his kinsman William Paget of Long Buckby. He left the rest to his wife – we don’t know how many.

Although Richard earned his living as a tailor, he seems to have had some livestock too, leaving a ewe and lamb to one of his step-daughters and a hoggrill sheep to his kinsman William Paget of Long Buckby. He left the rest to his wife – we don’t know how many. church bellringers – raising speculation that he may once have been one of their number.

church bellringers – raising speculation that he may once have been one of their number. In addition his five acres of land were to be sold when the eldest daughter Elizabeth came of age and the proceeds split between Elizabeth, her sister Mary and their brother Thomas. (William hoped that the land would fetch £30, giving them £10 each.) Having a few acres of land would have supplemented the family income, providing grazing for a few sheep, perhaps a house cow for milk, butter and cheese, as well as a supply of crops for income or home consumption.

In addition his five acres of land were to be sold when the eldest daughter Elizabeth came of age and the proceeds split between Elizabeth, her sister Mary and their brother Thomas. (William hoped that the land would fetch £30, giving them £10 each.) Having a few acres of land would have supplemented the family income, providing grazing for a few sheep, perhaps a house cow for milk, butter and cheese, as well as a supply of crops for income or home consumption. later. William appears not to have married, but Thomas, a tailor like his father, did, and when he came to make his will, early in the next century, he passed the five acres his father had bought down to the next generation of the family.

later. William appears not to have married, but Thomas, a tailor like his father, did, and when he came to make his will, early in the next century, he passed the five acres his father had bought down to the next generation of the family. He may have lived in it for a while, but in 1670 the parish register records the baptism of a daughter born to William and his new wife, Grace. And in that same year William sold the house to Edward Page, a baker, for £39.10s.

He may have lived in it for a while, but in 1670 the parish register records the baptism of a daughter born to William and his new wife, Grace. And in that same year William sold the house to Edward Page, a baker, for £39.10s.